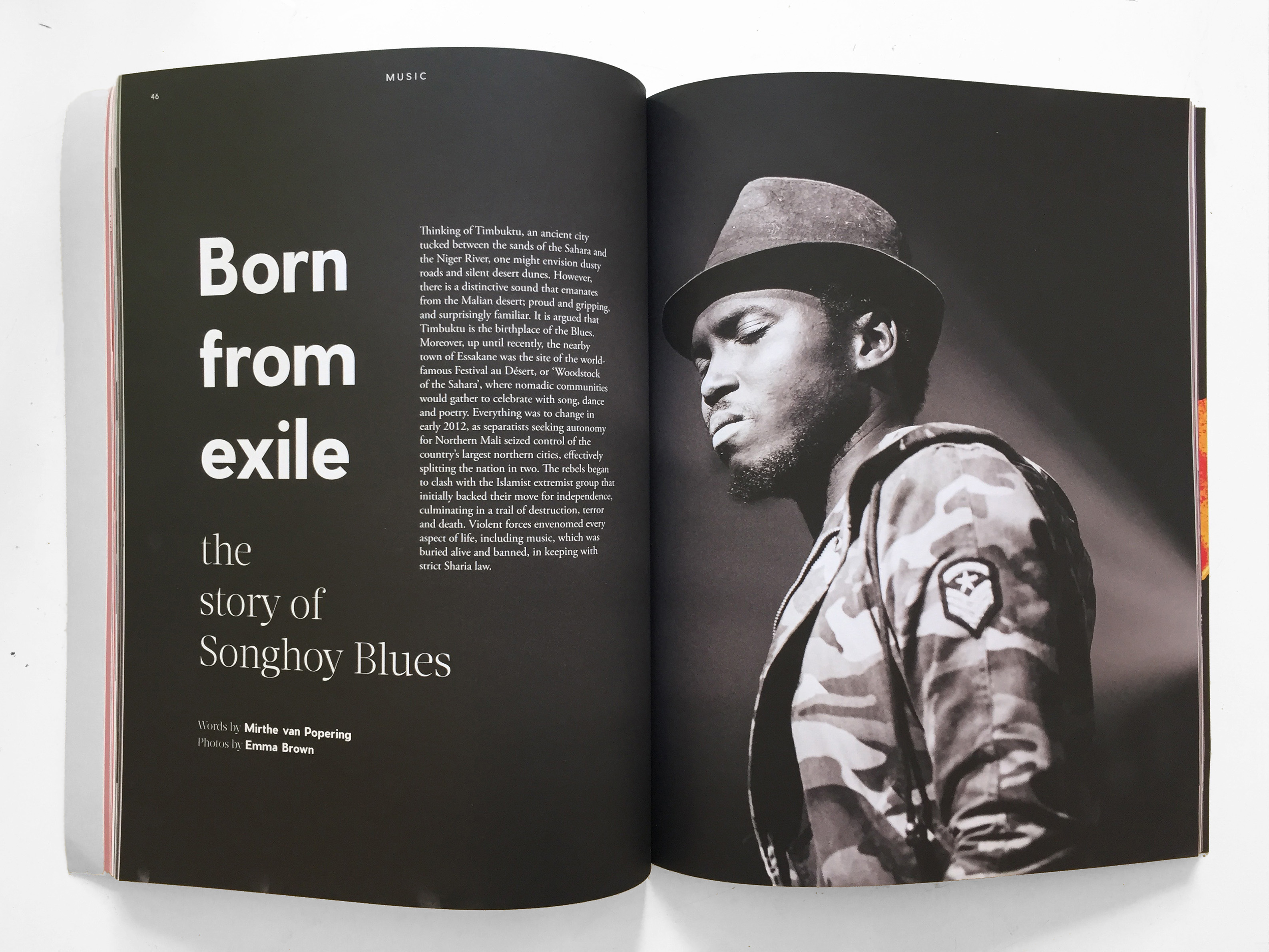

Born from exile • the story of Songhoy Blues

Thinking of Timbuktu, an ancient city tucked between the sands of the Sahara and the Niger River, one might envision dusty roads and silent desert dunes. However, there is a distinctive sound that emanates from the Malian desert; proud and gripping, and surprisingly familiar. It is argued that Timbuktu is the birthplace of the Blues. Moreover, up until recently, the nearby town of Essakane was the site of the world-famous Festival au Désert, or ‘Woodstock of the Sahara’, where nomadic communities would gather to celebrate with song, dance and poetry. Everything was to change in early 2012, as separatists seeking autonomy for Northern Mali seized control of the country’s largest northern cities, effectively splitting the nation in two. The rebels began to clash with the Islamist extremist group that initially backed their move for independence, culminating in a trail of destruction, terror and death. Violent forces envenomed every aspect of life, including music, which was buried alive and banned, in keeping with strict Shariah law.

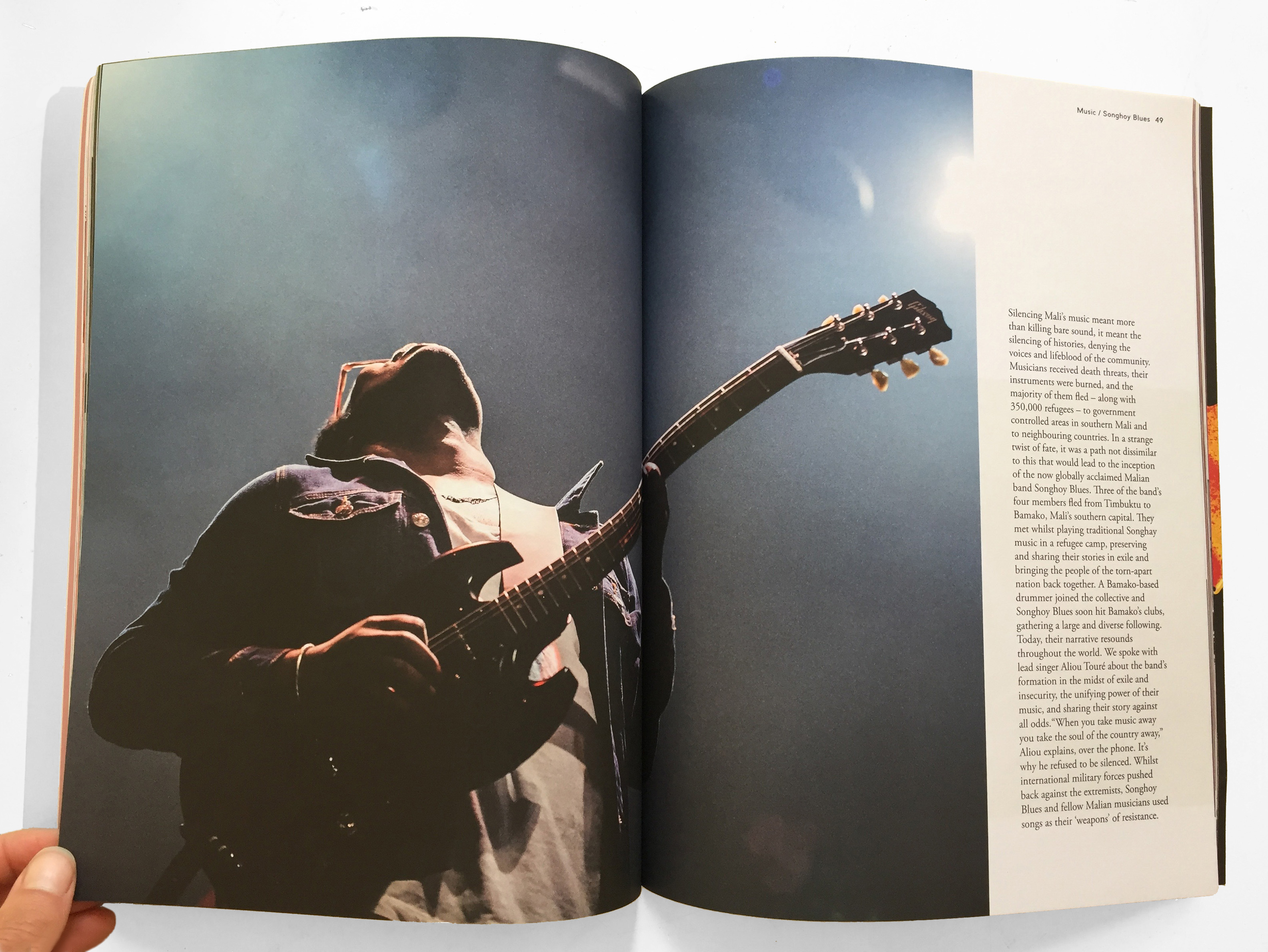

Silencing Mali’s music meant more than killing bare sound, it meant the silencing of histories, denying the voices and lifeblood of the community. Musicians received death threats, their instruments were burned, and the majority of them fled – along with 350.000 refugees – to government controlled areas in southern Mali and to neighbouring countries. In a strange twist of fate, it was a path not dissimilar to this that would lead to the inception of the now globally acclaimed Malian band Songhoy Blues. Three of the band’s four members fled from Timbuktu to Bamako, Mali’s southern capital. They met whilst playing traditional Songhay music in a refugee camp, preserving and sharing their stories in exile and bringing the people of the torn-apart nation back together. A Bamako-based drummer joined the collective and Songhoy Blues soon hit Bamako’s clubs, gathering a large and diverse following. Today, their narrative sounds throughout the world. We spoke with lead singer Aliou Touré about the band’s formation in the midst of exile and insecurity, the unifying power of their music, and sharing their story against all odds.

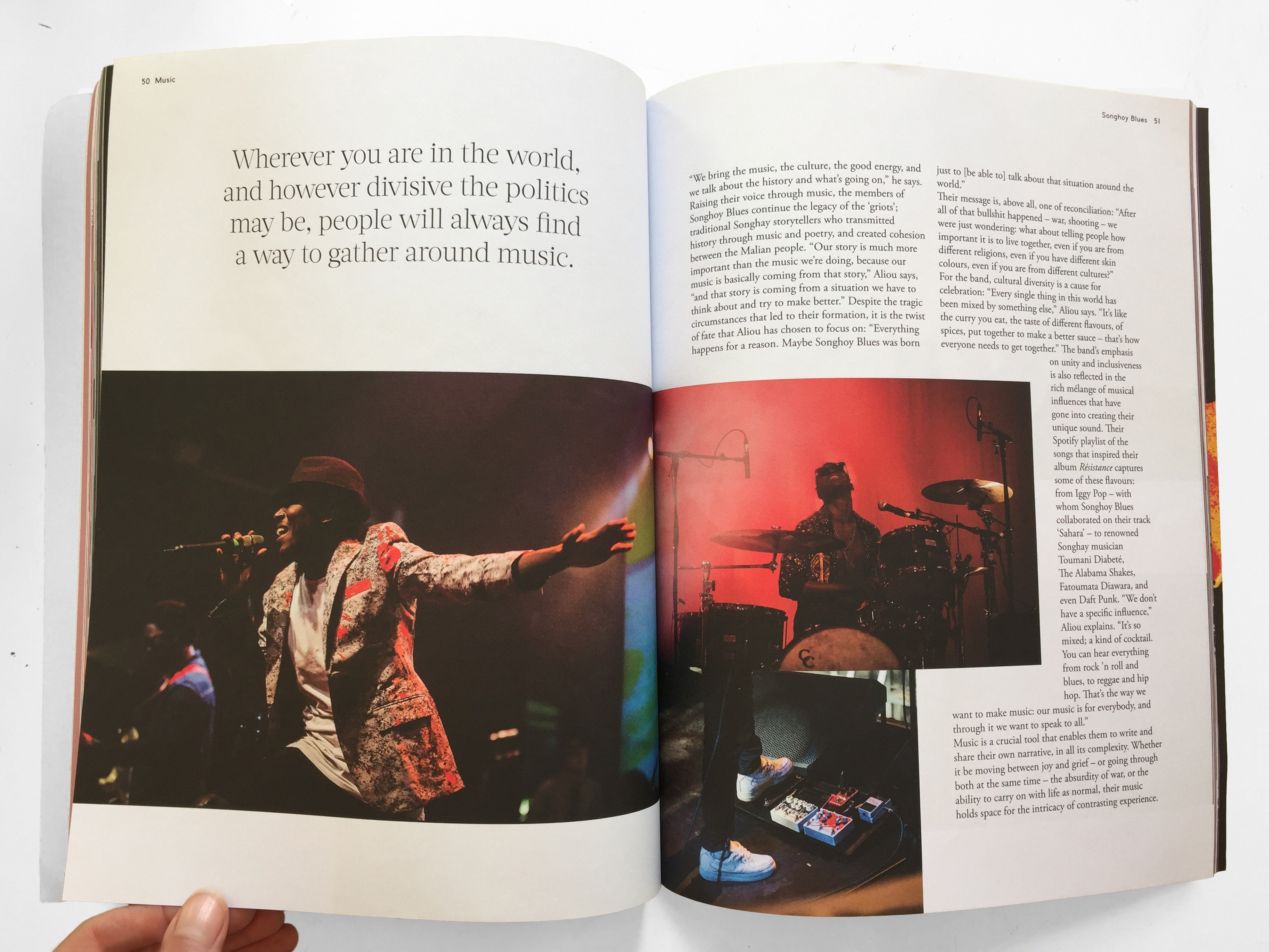

“When you take music away you take the soul of the country away,” Aliou explains, over the phone. It’s why he refused to be silenced. Whilst international military forces pushed back the extremists, Songhoy Blues and fellow Malian musicians used songs as their ‘weapons’ of resistance. “We bring the music, the culture, the good energy, and we talk about the history and what’s going on,” he says. Raising their voice through music, the members of Songhoy Blues continue the legacy of the ‘griots’; traditional Songhay storytellers who transmitted history through music and poetry, and created cohesion between the Malian people. “Our story is much more important than the music we’re doing, because our music is basically coming from that story”, Aliou says, “and that story is coming from a situation we have to think about and try to make better.” Despite the tragic circumstances that led to their formation, it is the twist of fate that Aliou has chosen to focus on: “Everything happens for a reason, maybe Songhoy Blues was born just to [be able to] talk about that situation around the world.”

Their message is, above all, one of reconciliation: “After all of that bullshit happened – war, shooting – we were just wondering: what about telling people how important it is to live together, even if you are from different religions, even if you have different skin colours, even if you are from different cultures?” For the band, cultural diversity is a cause for celebration: “Every single thing in this world has been mixed by something else,” Aliou says. “Its like the curry you eat, the taste of different flavours, of spices, put together to make a better sauce – that’s how everyone needs to get together.” The band’s emphasis on unity and inclusiveness is also reflected in the rich mélange of musical influences that have gone into creating their unique sound. Their Spotify playlist of the songs that inspired their album Résistance captures some of these flavours: from Iggy Pop – with whom Songhoy Blues collaborated on their track ‘Sahara’ – to renowned Songhay musician Toumani Diabeté, the Alabama Shakes, Fatoumata Diawara, and even Daft Punk. “We don’t have a specific influence,” Aliou explains. “It’s so mixed; a kind of cocktail. You can hear everything from rock ’n roll and blues to reggae and hip hop. That’s the way we want to make music: our music is for everybody, and through it we want to speak to all.”

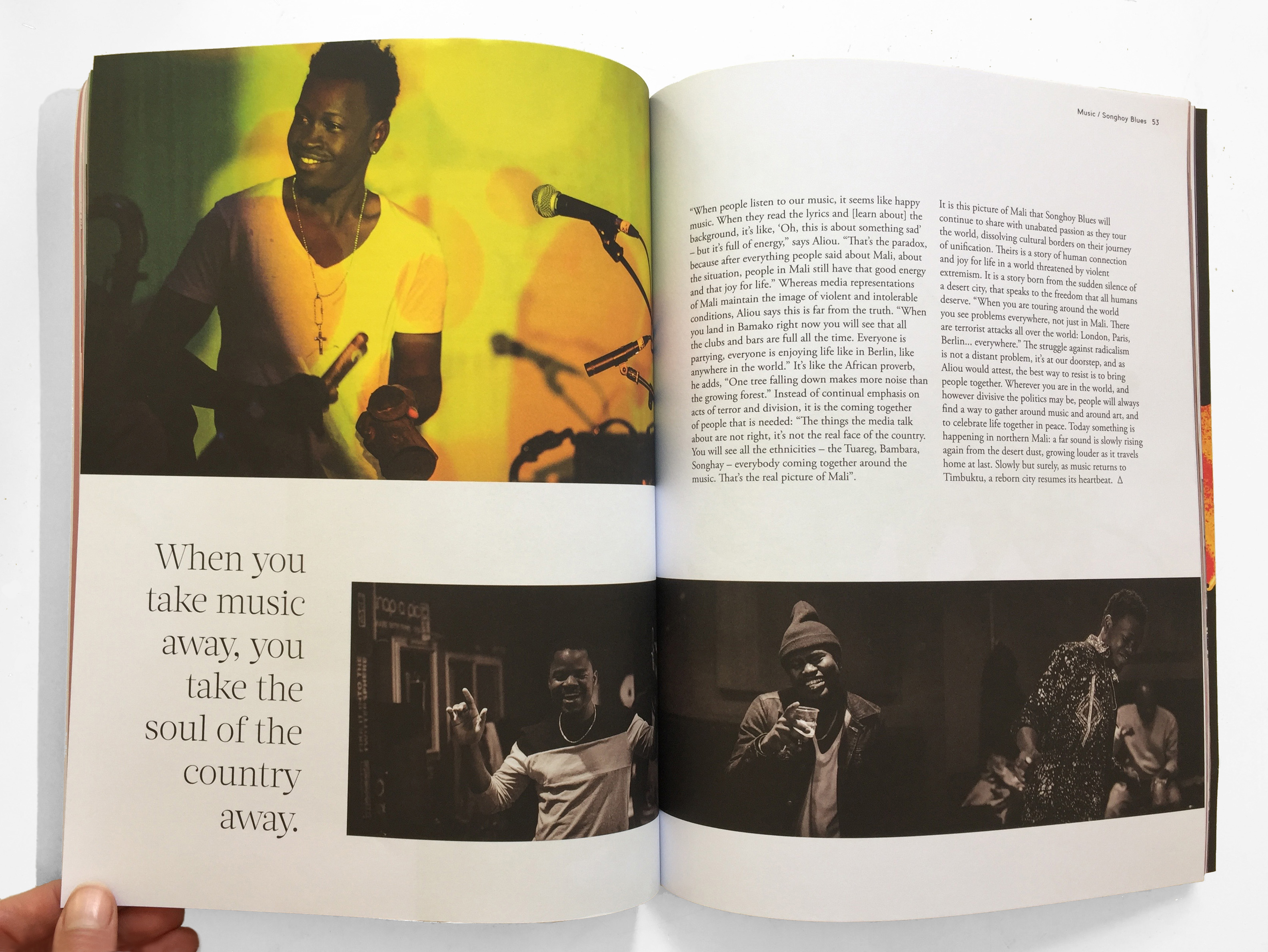

Music is a crucial tool that enables them to write and share their own narrative, in all its complexity. Whether it be moving between joy and grief – or going through both at the same time – the absurdity of war, or the ability to carry on with life as normal, their music holds space for the intricacy of contrasting experience. “When people listen to our music, it seems like happy music. When they read the lyrics and [learn about] the background, it’s like, ‘Oh, this is about something sad’ – but it’s full of energy,” says Aliou. “That’s the paradox, because after everything people said about Mali, about the situation, people in Mali still have that good energy and that joy for life.” Whereas media representations of Mali maintain the image of violent and intolerable conditions, Aliou says this is far from the truth. “When you land in Bamako right now you will see that all the clubs and bars are full all the time. Everyone is partying, everyone is enjoying life like in Berlin, like anywhere in the world.” It’s like the African proverb, he adds, “One tree falling down makes more noise than the growing forest.” Instead of continual emphasis on acts of terror and division, it is the coming together of people that is needed: “The things the media talk about are not right, it’s not the real face of the country. You will see all the ethnicities – the Tuareg, Bambara, Songhay – everybody together around the music. That’s the real picture of Mali.”

It is this picture of Mali that Songhoy Blues will continue to share with unabated passion as they tour the world, dissolving cultural borders on their journey of unification. Theirs is a story of human connection and joy for life in a world threatened by violent extremism. It is a story born from the sudden silence of a desert city, that speaks to the freedom that all humans deserve. “When you are touring around the world you see problems everywhere, not just in Mali. There are terrorist attacks all over the world: London, Paris, Berlin… everywhere.” The struggle against radicalism is not a distant problem, it’s at our doorstep, and as Aliou would attest, the best way to resist is to bring people together. Wherever you are in the world, and however divisive the politics may be, people will always find a way to gather around music and around art, and to celebrate life together in peace. Today something is happening in northern Mali: a far sound is slowly rising again from the desert dust, growing louder as it travels home at last. Slowly but surely, as music returns to Timbuktu, a reborn city resumes its heartbeat.

Published in PANTA Magazine • Issue 13

Photos by Emma Brown

PANTA was an independent magazine published from 2009 to 2013 that celebrated global creative culture and artivism. It featured the work of emerging artists and writers whose creative endeavors have the power to address social, political, cultural and environmental issues. Issue 13 includes interviews with queer scene photographer Pepper Levain and Aliou Touré, lead singer of Malian resistance band Songhoy Blues; a feature on the PangeaSeed Foundation, which gives voice to the ocean through art; and The Bomb, an immersive art installation that guides viewers through the strange reality of nuclear weapons today.